- Home

- Know

- A la carte

- The Trélazé slate quarries

The Trélazé slate quarries

Published on 13 April 2017 - Updated 16 November 2018

Age-old mining activities, knowhow and quality

In a manner of speaking, the little hills along the south side of the railway line, many of them scattered with broom, silver birch or oak trees, are Anjou’s slag heaps – but that’s not coal you’re looking at, it’s slate.

“Those hillocks are manmade – they’re debris, flaws, poor stone, poor-quality schist no good for manufacturing roofing slates, so they’re thrown away, piling up into mounds over the centuries, a dozen or more metres high.”

The slate here is extracted from the vein of schist that runs from Angers and follows the Loire Valley, passing through Trélazé along the way. The municipality’s slate quarries were closed down in November 2013; today, there’s a museum devoted to them, largely run by Jean-Christophe Boiteau and Emmanuelle Terrien.

“Slate quarrying here in Trélazé dates back to the late Middle Ages or thereabouts, as the first quarry in Trélazé dates from 1406; it was called Tirepoche.

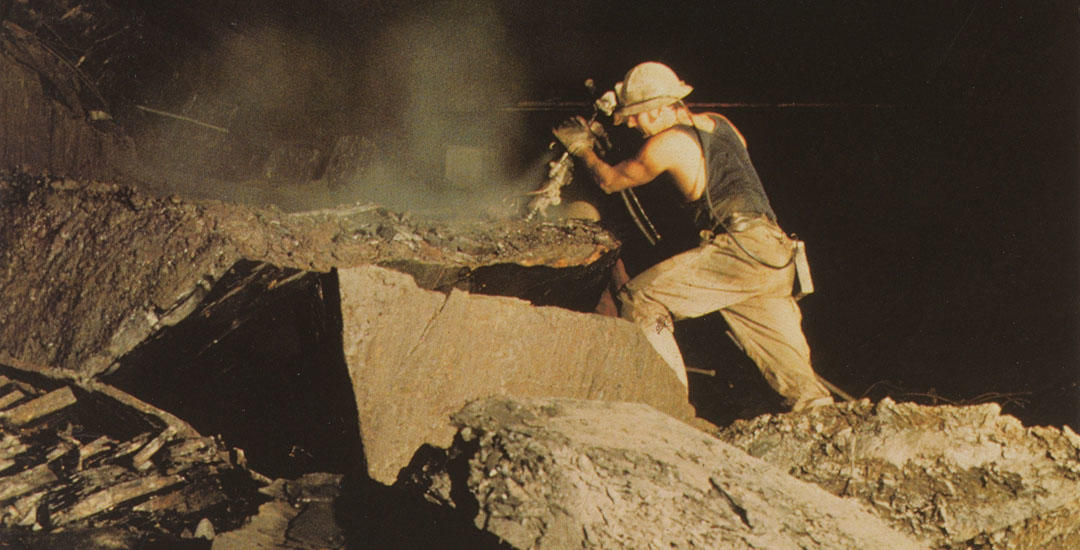

The rock, the slate that is, cropped out on the surface, so it could be extracted from open-air quarries. From the mid-19th century onwards, the techniques used – that’s to say, the introduction of the steam engine and electricity enabled deeper shafts to be dug; quarries shouldn’t really be more than a hundred metres deep as any more becomes too dangerous, but for underground mining, some shafts were up to 550 metres deep. When it was a matter of extracting slate from open-air quarries, the workers were known as quarrymen, “gadabas” or “perrieux”, and naturally enough, the people who received it to process it into roofing tiles were known as splitters or “gadaos”, and then the term “miner” came to be applied to workers who went down the shafts to the bottom of the mines.”

Whether underground or on the surface, work conditions were harsh, but the quality of the schist was worth the trouble and produced top-quality slate tiles.

“It is non-combustible and rot-proof, although not necessarily insulating – that’s not its strongest point. It’s impermeable though, of course, and it’s fissile, easy to split; it’s even flexible. Its mechanical resistance is greater than oak – in fact, it’s less easily crushed than granite.”

As to why slate was quarried here in Anjou, the reason’s simple enough.

“It was considered the purest deposit of all time, and the best slate in the world without a shadow of doubt; that was also why it was used so much on the Loire châteaux and other outstanding monuments of French architecture.”

![Nouvelles Renaissance(s] 2023](/var/storage/images/val-de-loire-refonte/dossier-de-parametrage/pied-de-page/nouvelles-renaissance-s-2023/517479-13-fre-FR/Nouvelles-Renaissance-s-2023_image_largeur220.png)

Lettre d'information

Lettre d'information

Facebook

Facebook

Flickr

Flickr

Podcloud

Podcloud

Dailymotion

Dailymotion

Box

Box

Slideshare

Slideshare

Diigo

Diigo